Thirteen cottages burning down was obviously a big deal for the families who were made homeless and lost nearly all their, uninsured, furniture and possessions. The buildings themselves were all insured so the impact on the owners was less catastrophic.

The fire started in the chimney of one of the cottages and was spotted almost immediately but due to the highly inflammable thatched roofs it ended up as a disaster. Thatch was the traditional way of roofing a house in Dorset and nearly all cottages would have been thatched when they were built. Fires were not unusual. Even so this seems to have been a big story which was not only covered by the local press but was reported across the country.

A trawl of the British Library’s Newspaper Archive shows that the day after the fire it was reported in newspapers across the nation. From Moray and Angus in Scotland, to Belfast, Yorkshire, Northumberland, Derbyshire, Warwickshire, London and Bristol. Over the next week or so the story appeared in papers published in Lancashire, Gloucestershire, Wiltshire, Devon, Somerset, Oxfordshire, Selkirkshire, Cornwall, Lincolnshire & Berkshire.

The most detailed account of the fire was published the day after in the Bridport News with the headline “A Disastrous Fire!” and it is largely from that account that it has been possible to pin down exactly where the disaster took place and identify some of the characters involved.

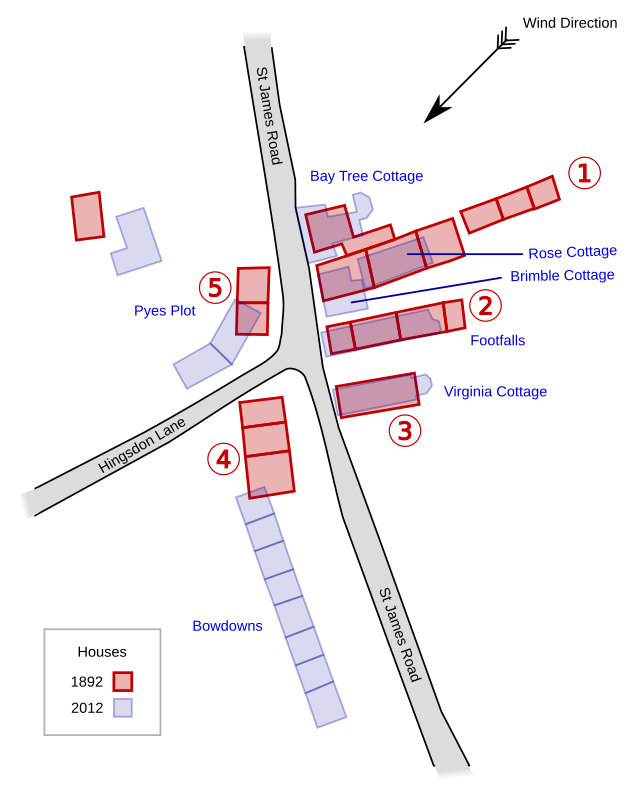

The location was in St James Road and we’re told that the houses that burned “formed an irregular group on each side of the road”. The account also says the fire “travelled an incomplete square” during which it was carried by sparks to “the other side of a narrow lane”. The most obvious candidate for the narrow lane is Hingsdon Lane placing the scene of the disaster around the junction of the two roads.

This is confirmed by the position of a property owned by William Read who features quite heavily in the Bridport News’ account. The building comprised “three slated cottages” … ”and there is no doubt the slated roof saved them”. After the fire had run its course it left “Mr. Read's houses standing uninjured in the centre”.

Thanks to the deeds for “Footfalls”, now in the possession of Hazel Evans, it’s been possible to confirm that this, slated, property was owned by William & Elizabeth Sarah Read at the time. William, a Tailor with a shop in the middle of the village, had acquired what is now Footfalls as the settlement of a debt of £100 in 1885 which he was owed by William Hine Martin who was described as a Butcher when he acquired the property in 1856. When it passed on to William Read it was valued at £105 and Martin was described as “out of business” having moved to South Kensington, London.

Edward Taylor, Master Thatcher of Chideock, has suggested that Footfalls would originally have been thatched “those higher gables with water tables (stones on top of the walls) is a big give away.” At some point prior to 1892 the original thatch must have been replaced with slates which was unusual in those days but turned out to be a wise choice.

The fire started in the chimney of one of several tenementRented dwelling

or lands in what is now the garden behind Brimble & Rose Cottages on the eastern side of St James Rd, opposite Hingsdon Lane. According to the Bridport News it was occupied by George Watts and was at the end of the row, that was almost certainly the eastern end, furthest from the road. Mr Walbridge, the Postmaster, spotted the chimney fire at “about ten minutes to eleven” and alerted the household. They closed all the doors and windows and threw salt on the fire but burning matter from the chimney caught the thatch alight.

This row of tenementRented dwelling

or lands, constructed to run perpendicular to the road, apparently contained four other households each of which seemed to occupy just four rooms.

According to the 1891 census, which was compiled about a year before the fire, George Watts (37) a Farm Labourer, his wife Sarah (44) and eight children (three sons and five daughters) aged from 8 months to 15 years made up the household where the fire started.

Also totalling ten was the Hawker family, John (32) a Coach Painter, his wife Rosalie (31) their seven children (five sons and two daughters) aged between 1 and 14 years plus Rosalie’s widowed mother Sarah Watts (70). Rosalie was the sister of their neighbour George Watts and Sarah was his mother.

Frederick Norris (30) a Tailor, his wife Louisa (21) and their 2 year old son had a bit more space between them (although we have no information about the size of any of the rooms).

James Budden (38) described in the census as “Formerly Millers Carter” and in the Bridport News article as “an invalid” shared with his wife Annie (25) and their two sons aged 1 and 3.

According to the Bridport News another victim of the fire was Thomas Travers, a labourer, but he isn’t listed in the 1891 census as living in the area. There are two Thomas Travers named in that census one a Blacksmith living in Waytown and the second, an Agricultural Labourer, was living in North Bowood with his wife, son, daughter-in-law and daughter. It is probable that it was this family from North Bowood that moved to St James Rd just in time to have their house burn down.

The report says the wind was blowing from the North East and this is confirmed by the Meteorological Office Daily Weather Report which records a strong breeze from the NE at 8am on that day. It carried sparks from the chimney or possibly the thatch of the Watts’ cottage over the slate roof of William Read’s house next-door. They didn’t have to travel far before they found another thatch on top of the house that is now called Virginia Cottage.

At that time this house was occupied by George Hodder and his wife Elizabeth as a dwelling and a bakery. All the other houses were only used as dwellings and, probably because it was also his business premisses, Hodder’s was the only one that had any insurance for the contents. Although this was undoubtedly a blessing it did result in complications later on.

Next in line were a couple of cottages on the western side of St James Road to the south of the Hingsdon Lane junction and a bit closer to both roads than the Bowdowns terrace which now occupies this plot and extends further south.

There must’ve been considerable concern about The Old Workhouse a bit further down St James Road but the wind direction seems to have taken any sparks or burning matter out across the field behind the cottages (Lower Bough Downs) because there is no mention of damage to the Old Workhouse.

The cottages that did catch were owned by Charles Watts and according to the 1891 census one of them was occupied by him (69) and his wife Mary (64). The other was the home of William Tolley (46), a Shoemaker, his two sons and a daughter aged 6 to 10.

By now the smoke and confusion must have made for a very chaotic scene. There was little prospect of any outside agency saving the situation. The Fire Brigade had been summoned from Beaminster but there were no telephones in the village until 1896 so a Dr. Webb had to travel to Beaminster Police Station, presumably by horse, to raise the alarm and the brigade didn’t arrive with their “small manual engine” until 12:15. The elapsed time and a lack of readily available water meant they were unable to make much difference.

The families living in the houses would have had very few possessions compared to nowadays but those they did have would have been very difficult to replace and none were insured so rescuing them would’ve been vital.

The newspaper reported “Chairs, tables, crockery, and bedding were thrown out into the gardens” but also notes that many of “the belongings of these poor, hardworking people” were “either destroyed by the devouring element or damaged or broken up entirely in the haste with which it was pitched out of the burning mass”.

The desire to salvage their belongings is illustrated in one incident involving considerable bravery. William Read, the owner of the slated house which didn’t catch fire, entered the smoke filled cottage of the seventy year old, Charles Watts, and went upstairs to find him attempting to extricate a bedstead. The news reporter asserted that “but for Mr. Read's assistance the probability is that Mr. Watts would have been stifled”. Despite the 28 year difference in their age William Read & Charles Watts had some pre-existing links and were probably friends as Read was named as an executor in Watt’s will which was drawn up the year before the fire in 1891.

The account in the Bridport News suggests that the fire then spread across Hingsdon Lane to two unoccupied houses more or less where 2 & 3 Pyes Plot are today before crossing back over St James Road to catch “the end house of the first row, and burnt itself back again to its starting point”. This seems unlikely bearing in mind this would’ve involved the fire travelling into the wind blowing from the North East.

Although a thatched roof is eminently flammable fire actually travels through the thatch quite slowly - “from 1.3m/hr in calm conditions to 4m/hr in a gentle breeze” according to the National Society of Master Thatchers. It seems probable that whilst everyone’s attention was drawn by the fire spreading to the houses to the south-west it was slowly making its way down the roof of the row of tenementRented dwelling

or lands where it started and it would’ve been sparks from that which caught the thatch of the two unoccupied cottages.

Regardless of how it actually spread the report said that “Within an hour from the outbreak most of the roofs had fallen in”. The fire brigade could only damp down Mr Read’s slated house in the middle and another house on the “Netherbury side of the first row” – presumably what is now Bay Tree Cottage. It’s hard to know how much effect this had but both buildings were saved even though the brigade ran out of water quite quickly.

Word reached the Bridport Fire Brigade at about two o’clock, some three hours after the fire was first spotted and although they “left at a gallop” they arrived too late to do anything useful.

The news report ends noting the considerable losses suffered by the burnt out families and saying they were being given temporary lodgings by their neighbours. It also points out “had the fire broken out in the night-time the result must have been appalling, as the conflagration was so fierce the people would not have had time to get out of their homes before the burning roofs had fallen upon them”.

In fact, despite the considerable loss of property, it was remarkable that no one died and there were no reports of injuries in “one of the largest fires that has occurred in the district for many years”.

The fire burnt itself out in less than three hours but there were repercussions that rumbled on for much longer.

- Fire starts in the chimney of George Watts’ house and embers catch the thatch alight.

- The slate roof of the house next-door, owned by William Read, does not catch.

- Sparks and embers carried on the wind spread the fire to the thatch on George Hodder’s house & bakery.

- With two thatches burning upwind the fire spreads over the road to the cottages occupied by Charles Watts & William Tolley and a third one which was unoccupied.

- Fire has spread through the thatch of the row where it started and now crosses the road to burn the two unoccupied cottages on the corner.